June 7, 2011

A Mariner 10 Perspective on MESSENGER: A First-person Account

Robert Strom

Forty years ago, in 1971, I became a member of the Mariner 10 imaging science team. This Mercury flyby mission was intended to gather atmospheric data at Venus and geological and geophysical data at Mercury in preparation for a Mercury orbiter mission. At that time we knew almost nothing about the innermost planet, and the Mariner 10 flybys were intended to help in the selection of an instrument payload for an orbital mission. The Mariner 10 spacecraft flew by Venus once and Mercury three times. Because of the configuration of the flybys and the orbit of Mercury, Mariner 10 imaged the same hemisphere of Mercury on each of its three flybys, for a total surface coverage of only 45%. Much of this coverage was taken with the Sun high in the sky, a situation that makes it difficult to see topography. As a result, we could perform geological analyses on only about 30% of the surface.

The technique of sending a spacecraft to orbit Mercury using multiple planetary flybys was discovered in the mid-1980s. However, the difficulties and expense of a Mercury orbital mission (estimated at ~$1 billion in 1985 dollars), coupled with a perception that Mercury was similar to the Moon and therefore of low scientific priority, meant that no such mission was developed for decades. It was not until the Carnegie Institution of Washington and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory devised a low-cost Mercury orbiter concept that an orbital mission was approved, as part of NASA’s Discovery Program. I am very privileged to be the only person on the MESSENGER Science Team who also participated in the Mariner 10 mission.

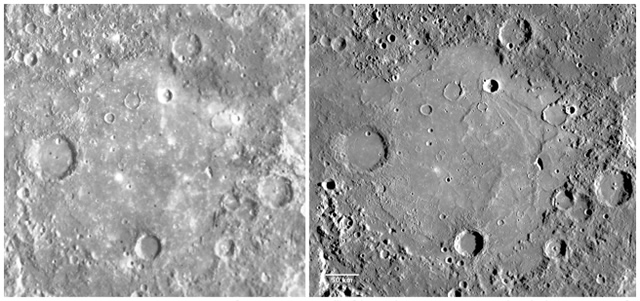

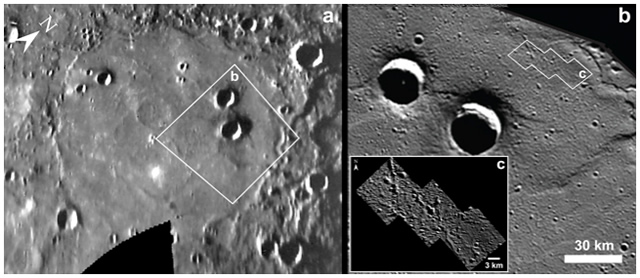

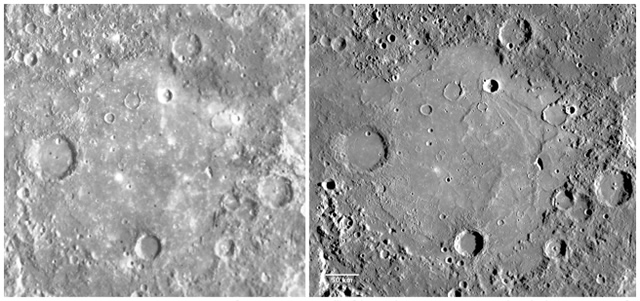

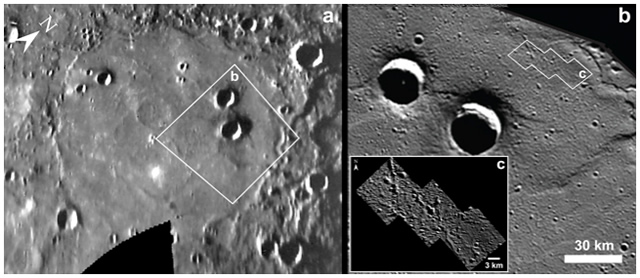

When MESSENGER went into orbit about Mercury on March 18, 2011, I was overjoyed. I had waited almost 40 years for that moment. When the spacecraft sent back its first images on March 29, 2011, the date was 37 years to the day after Mariner 10’s historic first flyby. What a coincidence! Since then I have been overwhelmed by the quality of the MESSENGER’s Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) images (e.g., Figures 1 and 2) and the data from the six other instruments on the spacecraft, and how much better they are than the Mariner 10 data. Although the Moon and Mercury are both heavily cratered surfaces, Mercury’s history is very different from that of the Moon, and the new images are making that extremely clear. The MESSENGER mission has started a new era in planetary exploration and will finally provide information that will allow us to better understand this strange and wonderful planet.

Figure 1. Comparison of Mariner 10 (left) and MESSENGER (right) images of the Tolstoj impact basin, approximately 350 km in diameter. The level of detail visible in the MESSENGER mosaic (~220 m/pixel) is much greater than that in the Mariner 10 mosaic (~1 km/pixel). MESSENGER will image more than 90% of Mercury’s surface at an average resolution of 250 m/pixel or better, a feat that could never have been accomplished by Mariner 10. MESSENGER is also taking higher-resolution targeted images at resolutions of 10-25 m/pixel!

Figure 2. Comparison of Mariner 10 and MESSENGER images of Goethe crater (383 km in diameter) in the northern plains of Mercury. The MESSENGER image labeled b on the right is at 200 m/pixel and shows the region within box b in the Mariner 10 image on the left. A portion of a targeted area (box c) imaged by MESSENGER at 12 m/pixel is shown in the inset labeled c. Mariner 10 was not able to obtain these types of high-resolution images.